The Eye of The Camera

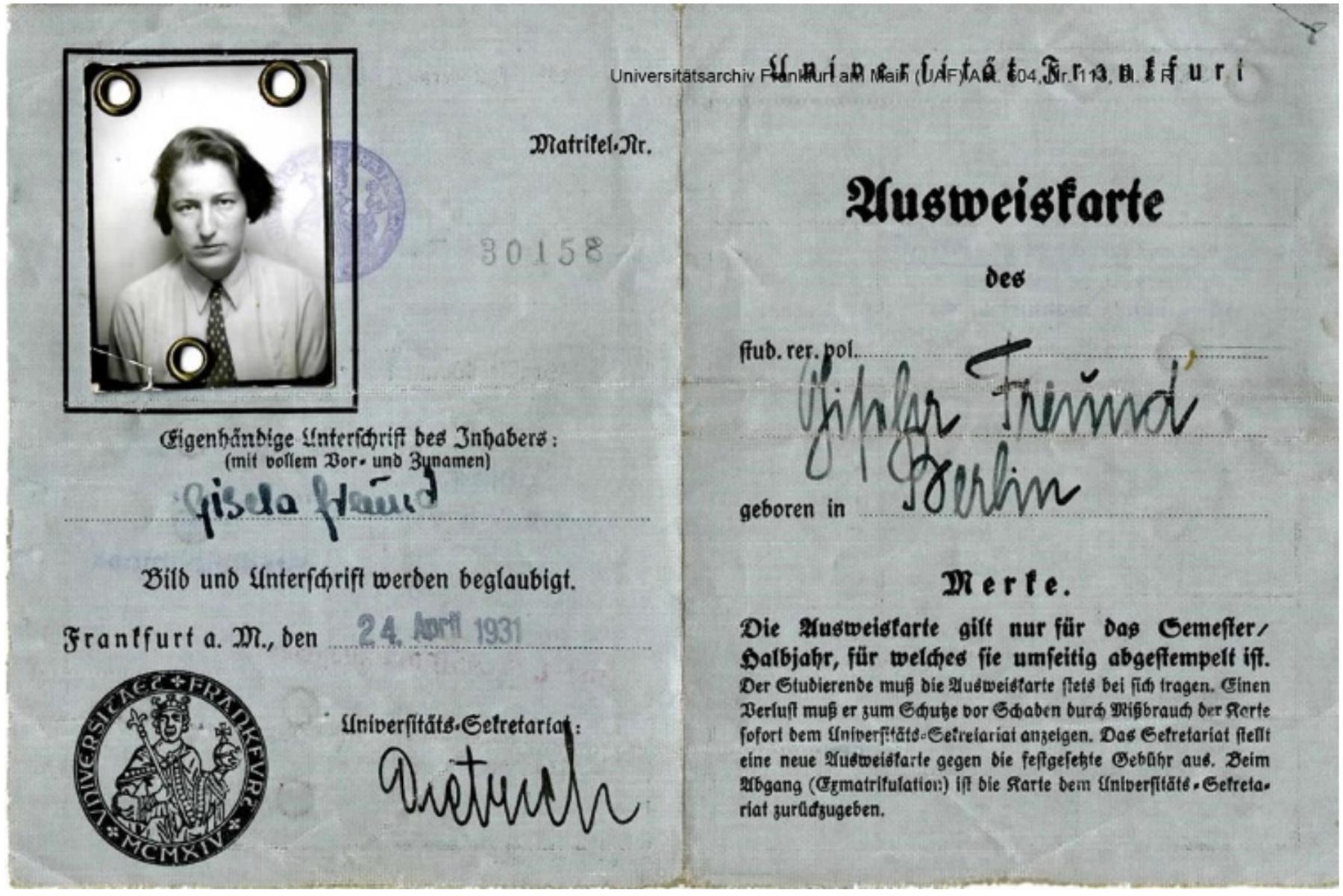

Gisèle Freund • 1974

A I never again went anywhere without my camera. It had become my third eye. B

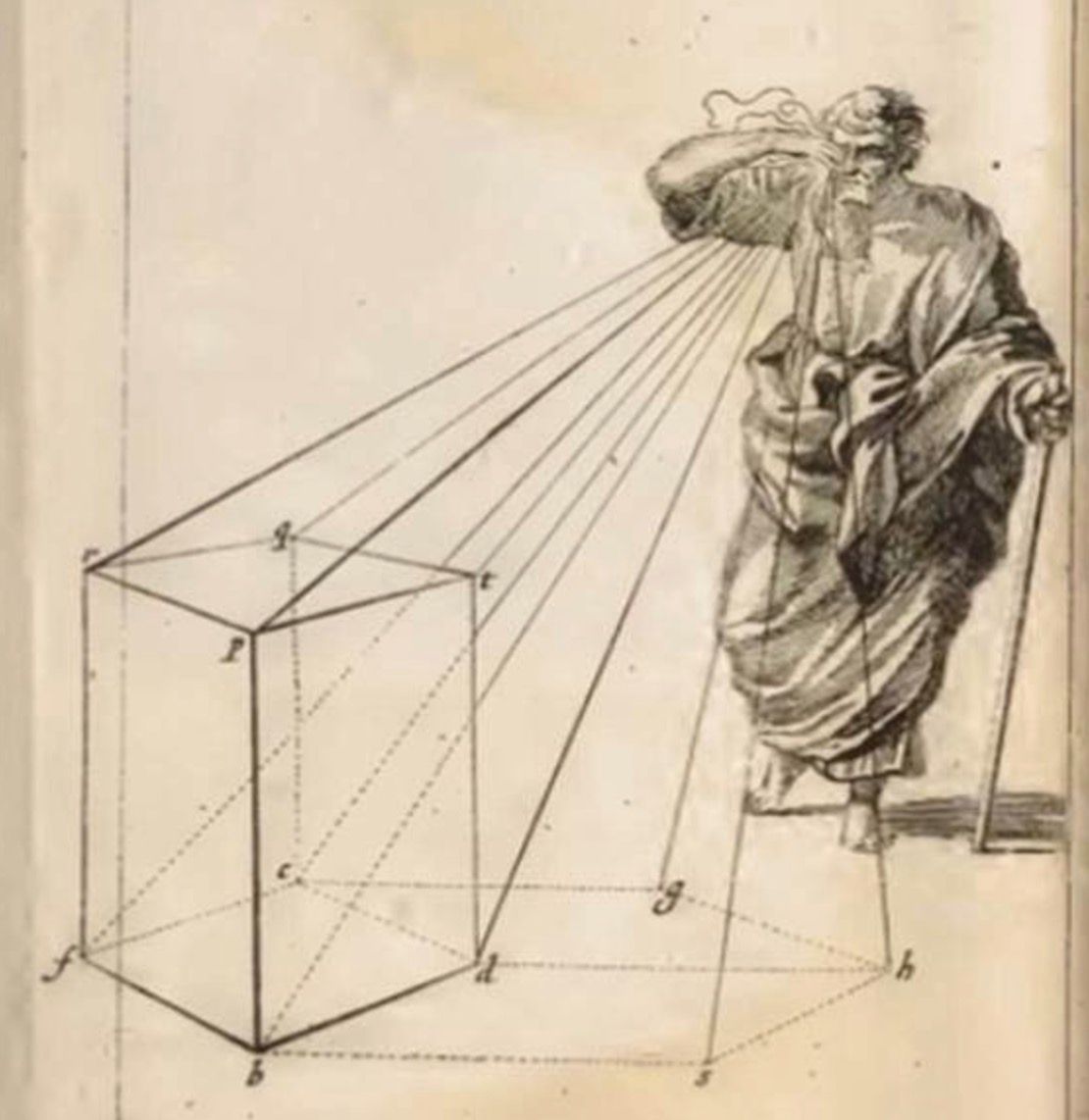

By almost imperceptibly shifting our eyes, we are able to see a whole group of things simultaneously. In one glance we take in not only the street but the houses, the sky, the passersby, and the gestures they make. There is the milkman, setting two bottles in front of the door across the street; next to me is the postman, in his blue uniform, delivering letters to my concierge. C I catch the curious look in her eyes as she makes out the various names and addresses; but that is not enough: she turns the envelopes over to find out who sent them. Up the street a beggar is asking for charity. He is blind, but only during the day, for I remember having seen him reading the newspapers one evening in a neighborhood café. The door of the corner bakery opens and out walks a housewife with two long loaves of bread under one arm and a net bag filled with food in her hand. It is almost noon; lunchtime is approaching. A truck loaded with furniture moves slowly down the middle of the street. True: it is September 30, and the second-floor tenants are moving.

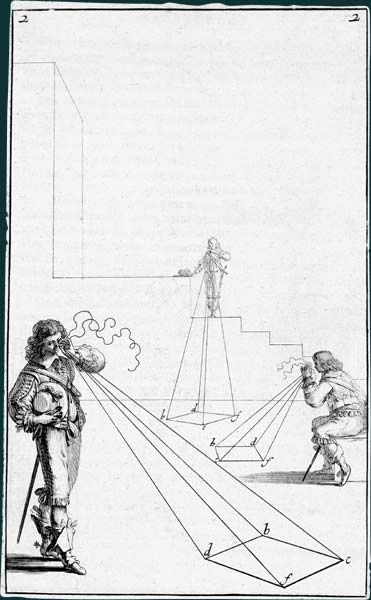

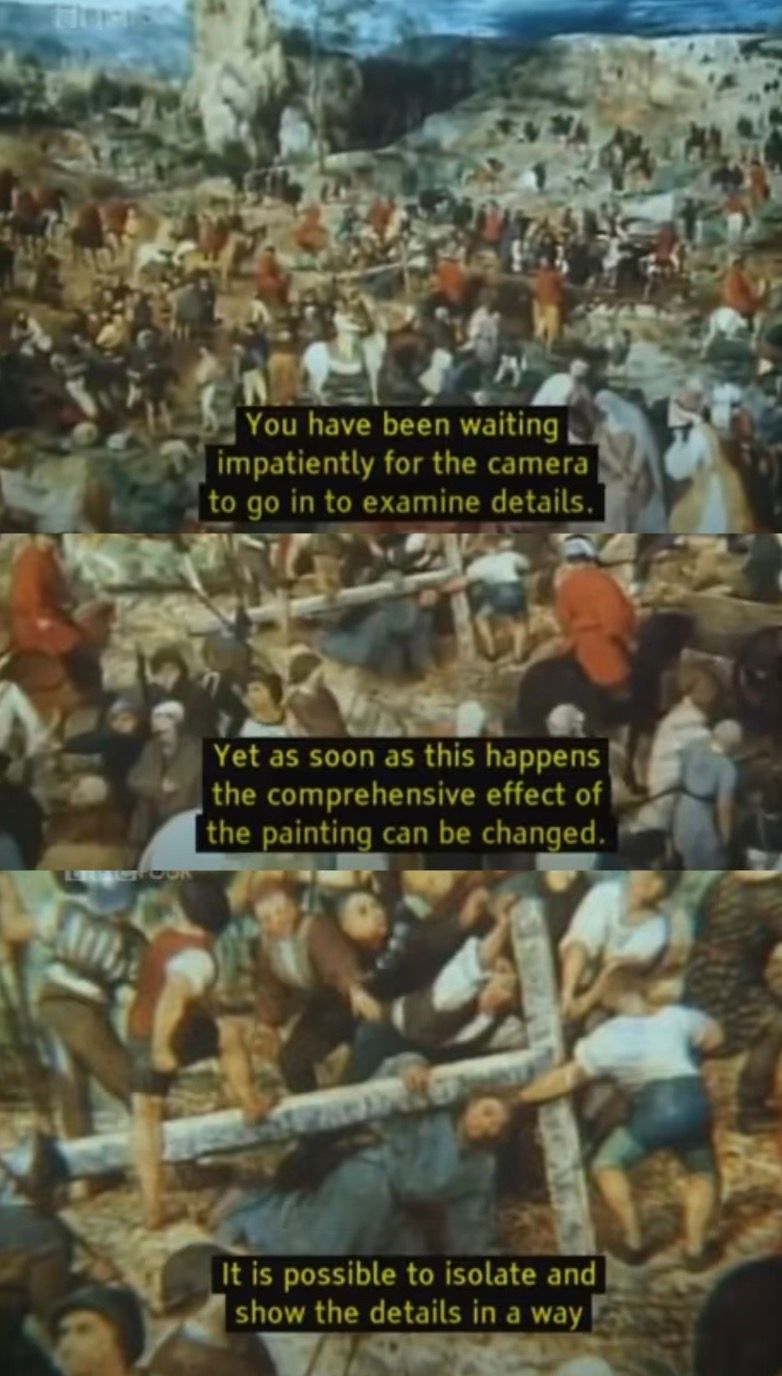

While the human eye absorbs innumerable details, the camera eye selects: therein lies its power, if one knows how to use it. E Aimed at the milkman across the street, it never wanders toward the postman or the concierge; the camera must choose between the beggar and the housewife, the vault of the sky and the pavement; it captures an isolated reality in a fraction of a second. F The immediate present thus takes on a symbolic value, which–if the photograph has meaning–awakens in the observer an endless series of associations of ideas and emotions. G

A photograph cannot go beyond what the photographer intended. 1 I am the one who decides at exactly what moment the button must be pressed. I choose the precise angle from which a scene will be taken. H Twenty photographers standing right where I am when I focus will see different images. Each individual, with his particular sensitivity, perceives the same subject in his own unique way. And in the end, the intrinsic value of the photograph depends on the photographer's ability to select, among a mass of impressive and jumbled details, those that will reveal the most meaning.

Technical knowledge is of small account; above all, one must learn to see. I

“I name that man an artist who creates forms and I call that man an artisan who reproduces forms, however great may be the charm or sophistication of his craftsmanship,” said André Malraux J in his Voices of Silence. A photographer can master all the tricks of his trade and produce a technically perfect photograph; if his picture is interchangeable with anyone else's, no matter how good a technician he is, he is merely an artisan.

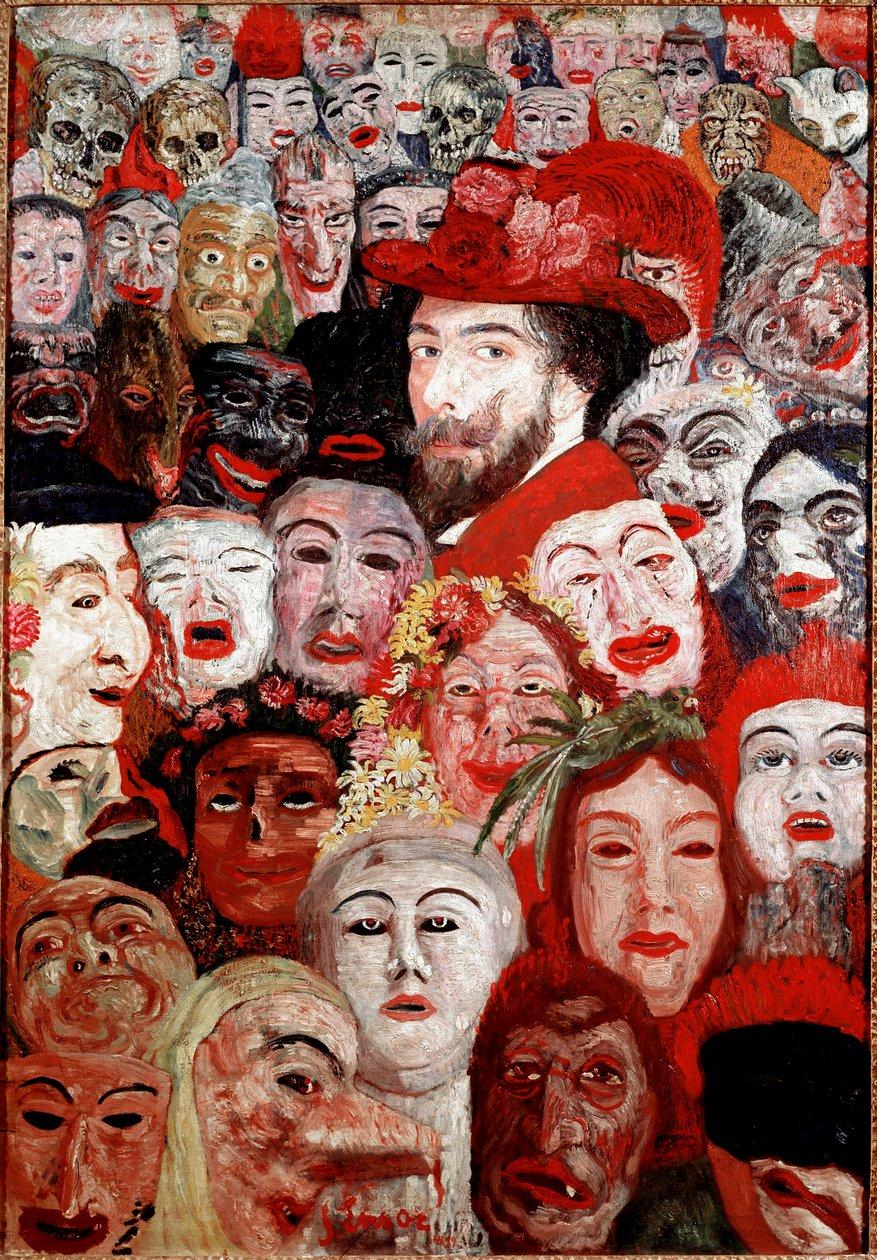

I had wanted to be a sociologist because the extreme diversity of social problems fascinated me. I became a photographer out of necessity, but I have never regretted it, for I soon understood that my most vital concerns were directed toward the individual, with his sorrows and hopes and anguishes. K My camera led me to pay special heed to that which I took most to heart: a gesture, a sign, an isolated expression. Gradually, I came to believe that everything was summed up in the human face – an inexhaustible panorama to which I finally devoted myself. L In order to gain experience in making portraits, I invented a little game.

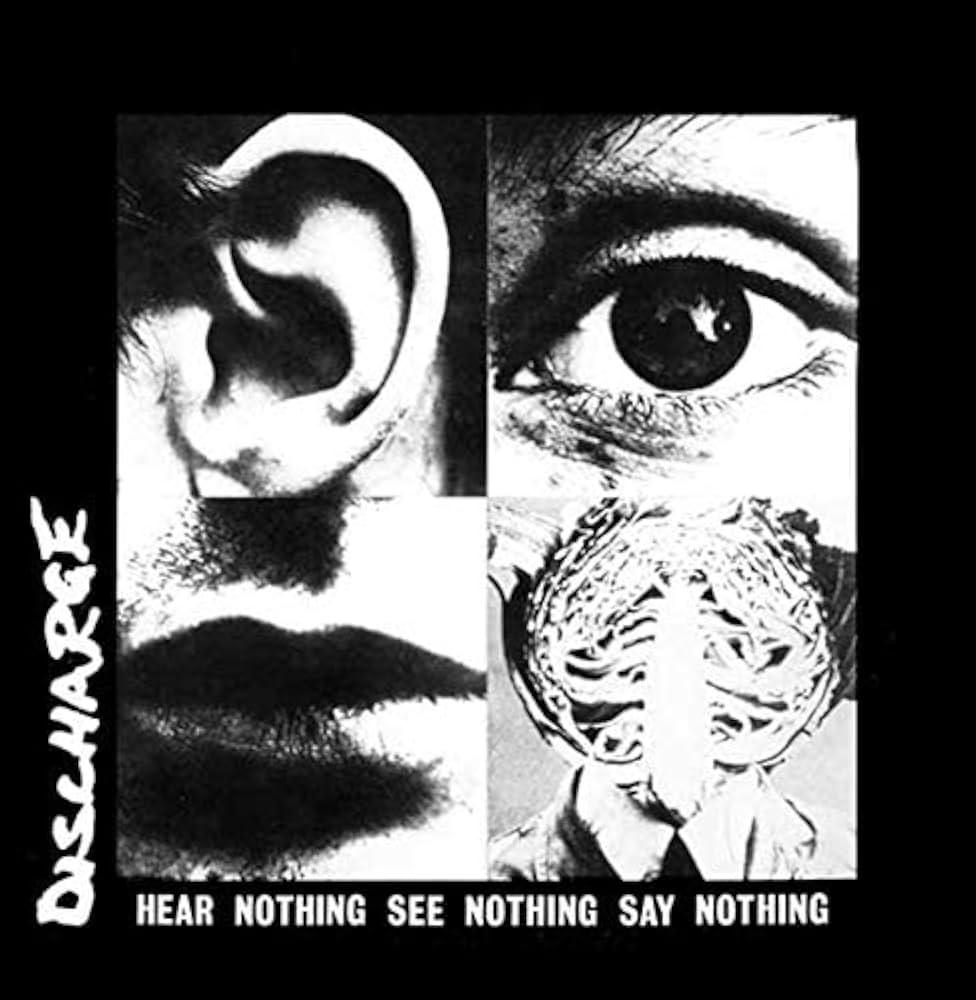

Till then, the crowds that flooded the subways and the parks, M the buses and the boulevards, had been no more to me than a dense mass of anonymous and indistinguishable faces. What I started to do was examine each passing face. In the subway I would observe a workman sitting across from me, prostrate with fatigue. I would concentrate on one detail: eyes, for example, or else the nose, the forehead, or the chin, as if all the rest were hidden under an imaginary mask. N By thus discreetly studying the faces that chance had set before me, I began to grasp the importance of detail, the symbolic essence of the individual: an imperceptible quiver at the corner of a contorted mouth, a wrinkle on the forehead, a furtive wink, a heavy eyelid. Sometimes just the expression in a man's eyes tells us more than his whole body. O

Yet to my mind the most profound secrets are revealed by the mouth, for it is the most difficult part of the face to control. Look at the lips of that six-year-old child–full lips, half open: they show an absence of any distrust and a curiosity about men and things. For her the world is still filled with miracles and the unknown. The young woman sitting next to her, holding her hand, has a thin, tight-lipped mouth. The corners of her lips, drawn slightly down, express a hard life burdened with care. However rigid her bearing, she is betrayed by that detail. Q

The huge procession of faces that have paraded before me and which I shall never see again has made me aware of the fact that no two physiognomies are alike; R indeed, it is rare to find two that are even somewhat related. A painter can take all the time he wants to immobilize the subtleties of a personality on canvas. Like a hunter S, the photographer has no more than a moment; he must lie in wait for his prey and swiftly catch the revealing expression. Once the photograph is taken, he moves out of sight. Our first thought in front of a good painted portrait is to ask the painter's name. But in photography it is the model that counts, and the role of a good photographer is to be the sensitive instrument T by means of which a personality is revealed.

Notes

From the moment the professional photographer sells the reproduction rights to his photos to the press, television, or advertising, he is no longer in control of their presentation. The meaning of a photograph can be changed in all sorts of ways. An image can come to represent the opposite of what the photographer intended to show, thanks to retouching, the accompanying caption, and a host of other means. Thus photography, in the hands of those who make use of it, can become an allpowerful method of propaganda. Hundreds of millions of amateur photographers have no inkling of this. They go on believing that photographs are exact copies of nature and of human beings. Don't they have the proof of it from their own experience? The pictures of Johnny on the dresser—as a baby, taking his First Communion, as a soldier, a bridegroom, the father of children—were they not taken by his intimates? They show Johnny to perfection at the various stages of his life. From this people deduce that the photos they see every day in magazines and on the television screen express the truth. They do not realize that they often present a falsified, manipulated reality. (Giséle Freund, Photographer, 1985, Introduction)